Small Cave Hotel in the heart of Cappadocia

ASMALI CAVE HOUSE

CAPPADOCIA (Kapadokya)

The magical wonderland in the heart of Anatolia

The area of Cappadocia has gained its present fame thanks to the strong interaction of nature and history, the combined forces that have created the main characteristics of the region.

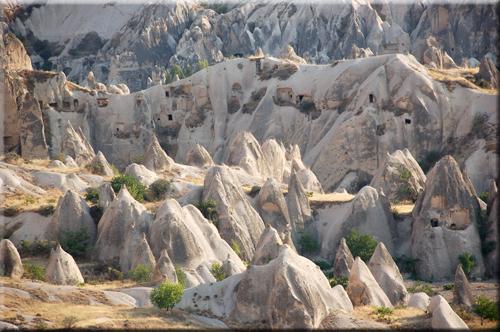

Sixty million years ago when the nearby massif folded upwards, towering volcanoes arose. Ten million years ago, three of those volcanoes, Mount Hasan (3,268m), Melendiz Mountain (2,898m) and Mount Erciyes 3,917m) erupted, covering the entire area with a thick layer of lava. This, mixed with ashes and sand, along with the occasional layer of basalt, formed a high plateau. After the strata of soft tuff then hardened, wind and rain took the next step in creating this geological wonderland.

HOW NATURE CHANGED THE LANDSCAPE OF CAPPADOCIA

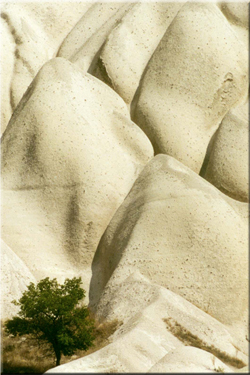

For the thousands and thousands of years since, erosion has been the primary force of change consistently transforming the face of the area. Various volcanic materials, different in density and thickness, are affected differently by the different agents of erosion.

While wind has a rounding effect, rivers and streams change shapes vertically; rain does so horizontally. Knowing the effect of each eroding agent makes it easier to understand how deep canyons, the softly flowing stone formations of hills and inclines, as well as the shapes of the fairy chimneys came about.

While wind has a rounding effect, rivers and streams change shapes vertically; rain does so horizontally. Knowing the effect of each eroding agent makes it easier to understand how deep canyons, the softly flowing stone formations of hills and inclines, as well as the shapes of the fairy chimneys came about.

Different types of rock are eroded into entirely dissimilar shapes. Basalt, harder than tuff, is not affected easily by erosion, so that where a protecting layer of it exists on top, the tuff underneath erodes much more quickly, and a veritable forest of rock needles arises, resembling a huge hall with columns, covered by a ceiling of basalt.

With the erosion of the tuff, the support underneath the basalt decreases and large parts of the basalt cover break off while others remain, like caps on single standing formations. Today these objects give the impression that they were built by human hand, but in reality, these masterpieces were created by Nature. Humans, however, have taken what evolved naturally to produce other wonders - the rock churches and underground cities of Cappadocia.

THE BORDERS OF CAPPADOCIA

The exact borders of Cappadocia have been a topic of dispute among historians. However, it is generally agreed that the area between Kayseri in the East, Aksaray in the West, Niğde in the South and Kırşehir in the North marked the four corners of the former province, its heartland being the triangle from Ürgüp to Avanos and Nevşehir. The first signs of settlement in the region date from approximately 8000 BC (...). Many different rulers conquered the area, from the Hittites and the Phrygians to the Lydians, until about 546 BC the area fell under Persian power (...) and was divided into administrative districts with the western part of Anatolia referred to as Katpatukya.

THE FIRST CAVE DWELLINGS

This period marks the first mention of underground cities. In the early stages of their development, these underground sites were used for storage purposes only, but as they were enlarged, they also began to serve as places of refuge during times of potential danger (...). During the 4th century AD, Christianity gained strength in the Byzantine Empire.

In

Cappadocia, at first small caves were used by religious hermits or

eremites. Later, large churches were carved into the tuff, hidden behind

thick stone walls and sometimes visible from the outside only by virtue

of small window. At the same time, caves began to provide housing and

refuge during battles and invasions as well (...). With time, small

Christian communities in the area grew into villages and the churches

became highly frequented. Later, with the ongoing Illumination, the

number of Muslims increased.

In

Cappadocia, at first small caves were used by religious hermits or

eremites. Later, large churches were carved into the tuff, hidden behind

thick stone walls and sometimes visible from the outside only by virtue

of small window. At the same time, caves began to provide housing and

refuge during battles and invasions as well (...). With time, small

Christian communities in the area grew into villages and the churches

became highly frequented. Later, with the ongoing Illumination, the

number of Muslims increased.

Although

Christianity and Islam lived in a mostly peaceful co-existence, many of

the Orthodox, Catholic and Protestant Greek and Armenian population

chose to gather in particular villages. This meant that in some areas,

churches as well as monasteries were deserted as minority Christian

populations left for the enclaves of such villages. No longer used as

sanctuaries, these dwellings became homes for Muslim families.

Extracts from the book Uçhisar Unfolding by Evelyn Kopp